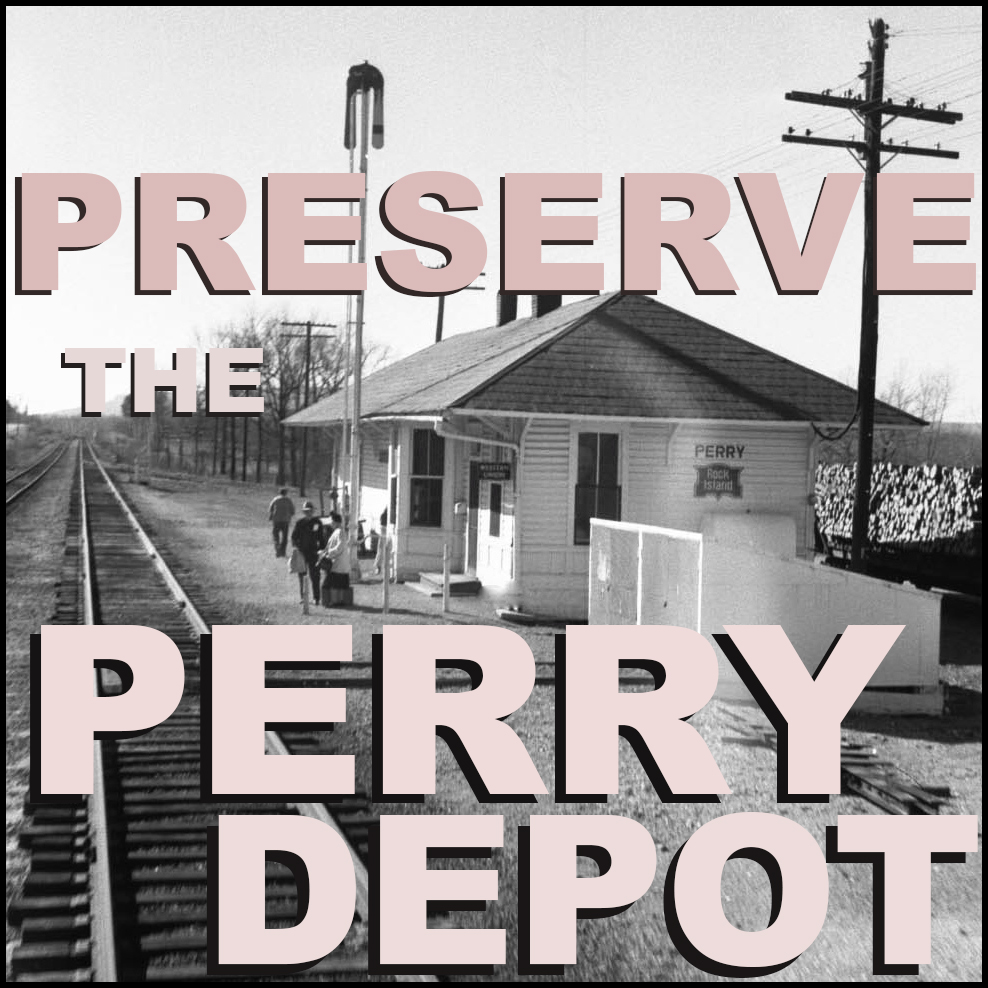

February – August 1989

KBBA-AM 690 was where I had my first paying radio position. At least it was supposed to be. But the station still ended up being a good learning experience, while exposing me to the harsh realities facing the industry.

Michael Hibblen on the air at KBBA on August 14, 1989. All music was played from records and I had one hand ready to start another song playing. The 45s In the background were current hits that were in heavy rotation. Photos: Dena Gardner

I heard about the job from Bob Gay, my high school broadcasting instructor, who said he thought the small station would be a good starting position for me. I had been volunteering at Little Rock community radio station KABF-FM 88.3 a few months by then and was hoping to get a paying radio job somewhere. Apparently KBBA owner John Riddle had called my teacher looking for cheap talent and hired me along with two other students.

The station, whose call letters stood for Keep Building Benton Arkansas, broadcast with a power of 250 watts in the day and 73 watts at night. The studios were located at 1100 Military Road, Suite 5, at the side of a large furniture store building. When I walked in for my job interview, I was immediately struck by how old and outdated the equipment was. At a time when CDs had taken prominence at most stations, KBBA was still playing 45 RPM records. The turntables, control board and cart machines were probably several decades old.

I was surprised there wasn’t a receptionist, with a DJ coming out of the control room to tell me Riddle was out on a sales call. I waited at least a half-hour before he called to say he wouldn’t be able to make it back because he was trying to close a deal with a potential advertiser. We talked on the phone a few minutes with Riddle telling me what the position entailed and I started the next night.

My shift was 5 to 10 p.m., when I’d sign the station off and shut down the transmitter. I followed a tight format clock, playing a mix of current and classic country music, along with national news from ABC, state news from the Arkansas Radio Network and state sports from the Creative Sports Network in Conway. I also anchored local newscasts during my first two hours. When I started, the station had someone who wrote local stories and gathered sound. During my first week, the big local story, which we stretched over several days, was about a mailman being attacked by a dog. We had sound bites every day from a spokeswoman for the U.S. Postal Service detailing the injuries, updating the man’s condition and calling for dog owners to secure their animals.

I really enjoyed anchoring newscasts, which involved me stacking carts with actualities and carefully coordinate them with pages of copy. At first, I would read every single story we had, sometimes stretching the newscasts to 15 minutes. I was told by Riddle to try and keep them to five minutes because they were airing after state, then national newscasts. Also, many of the stories had been running since the morning. But local news stopped after the news director quit because he, like the rest of us, was not getting paid regularly.

The only time it seemed KBBA had a significant number of listeners was during local high school sports broadcasts, with Riddle providing the play-by-play. During one broadcast, a problem with the transmitter knocked us off the air and I was inundated with phone calls from people trying to hear the game. We also had a higher caliber of advertisers during the sports broadcasts.

AUDIO: KBBA aircheck from June 23, 1989, beginning at 5 p.m. It was a Friday with meant we aired additional features.

KBBA also featured “Tradio,” a show once endemic to small town stations, in which listeners would call in and announce things they had for sell, how much money they wanted, and gave a phone number for anyone interested to call. Airing weekday mornings at 8 a.m., it was almost surreal to hear one caller after another trying to sell what was often junk. A typical example would be, “I’ve got a 10-year-old 19-inch TV. The color doesn’t work anymore so I’ll take $5 for it.” Or sometimes I heard people say they had a litter of kittens that were free to good homes. It was like classified ads on the radio and people seemed to love it. For the entire hour, there would be one caller after another.

I was excited to get my first paycheck for a couple hundred dollars, but quickly learned how bad things were at the station when it bounced. My parents, who deposited the check in their account and had given me cash, didn’t tell me until my second check was also returned for insufficient funds. But I kept working after being assured by Riddle I would eventually be paid what I was owed.

I knew I wasn’t alone. None of the other employees were getting paid regularly. I would frequently come in to find Program Director Bill Haywood, whose airshift was 9 a.m. to 5 p.m., fuming about needing money to pay his bills. But he would get some money occasionally or would be enticed with whatever would keep him showing up for work. In particular, once he showed me a gold Gruen wristwatch he had been given by Riddle, which the station had likely gotten free as a promotional item by the company. In exchange, KBBA plugged Gruen whenever the time was mentioned on the air, saying “It’s 5:10, Gruen precision time.”

Standing in front of a banner and the cart rack for commercials in KBBA’s control room on August 14, 1989.

Another promotional item the station would get free were boxes of macaroni, and — epitomizing how meager KBBA was — we would give away individual serving size boxes of macaroni as prizes for contests. Listeners would call in and win, but rarely did anyone actually come to the station to pick it up. The boxes would remain stacked in an office.

I don’t doubt that John Riddle was trying his best to sell commercials, he just couldn’t secure any significant advertising. It was hard for KBBA to compete with Little Rock stations that were booming in with stronger signals and better programming. The key to survival for stations in that situation was to be as local as possible, but that took having staff to produce that programming. Also, most AM stations by that time had stopped playing music as FM, with its better fidelity, had became dominant.

At one point, Riddle started selling 15-second advertisements for a dollar each, or as we called the practice, “a dollar a holler.” Commercial breaks then became more difficult for the air staff because we only had two cart machines to play them in. The 15-second commercials were on 40-second carts. One commercial would end before the previous cart had cued up and you couldn’t get the next one in, which resulted in brief moments of dead air. All the ads were was for small locally-owned businesses like dry cleaning, piano tuners and repair shops who Riddle said wouldn’t pay after receiving an invoice for their first billing cycle.

In another sign of how the station was struggling, we lost our affiliation with the Arkansas Radio Network for nonpayment. Haywood told me engineers from ARN came and took down thier satellite dish, which was also our source for ABC News. To fill the void of national news, the Creative Sports Network — which I guess was being paid something and came via some kind of phone connection — agreed to feed the Mutual Broadcasting System when its own programming wasn’t on the air.

I remember one night Riddle and his wife spent several hours working on the station’s accounting, then after leaving, stood talking in the parking lot in what seemed like a very serious, depressed state. I knew there was no way the station would survive much longer. Riddle’s late father had a role in the station’s early days and later became owner. I think he wanted to keep it going for the sake of family, but just wasn’t able to make a profit or even break even.

HISTORY OF KBBA

A construction permit for the station was granted on Nov. 9, 1951, according to documents from the Federal Communications Commission. KBBA’s first day on the air was June 26, 1953. It was owned by the Benton Broadcasting Service, which was made up of G. Lavelle Langley, Sam Preston Bridges, James B. Branch, Roy M. Fish and W. Richard Turk, Jr. Bridges sold his interest in KBBA to Langley in 1963 and would soon put a competitor, KGKO-AM 850, on the air. By May 8, 1963, assignment of the license, still doing business as the Benton Broadcasting Service, was to J. Winston Riddle, Melvin P. Spann and David C. McDonald. It appears J. Winston Riddle was sole owner by 1969.

Except for the times we would draw a sizable audience airing high school sports, it seemed most of our listeners were residents of a Benton nursing home who would call in and make requests. One person in particular named Berta would call almost nightly, sometimes several times, always requesting the same handful of songs: Willie Nelson’s “Blue Eyes Crying In the Rain,” Mark Gray and Tammy Wynette with “Sometimes When We Touch,” Mark Gray’s “It Ain’t Real If It Ain’t You,” and Kenny Rogers’ “Daytime Friends.” I even recorded her once and used it for a station promo. I asked her if she would say something good about the station and without further prompting she said, “I think KBBA is the best radio station in the world.” I’m sure she meant it. I guess I was glad someone thought so.

AUDIO: Two KBBA promos produced in July 1989 featuring Berta and another woman from a nearby nursing home.

A $100 bill John Riddle gave me on July 27, 1989. It was so rare to be paid that I photocopied it to remember the occasion.

About once a month John Riddle would give me a little cash, maybe a few $20 dollar bills. Toward the end of my six months there, I went a couple of months without being paid anything. Eventually he gave me a $100 bill, which I photocopied to mark the occasion. Yes, I saved that photocopy all these years. Overall, I was only paid a tiny fraction of the minimum wage salary I was owed. But I was doing better than the two other students Riddle had hired from my radio class.

One, Paul Benton, worked 12 hour shifts on Saturdays and Sundays, 6 a.m. to 6 p.m., and I think hardly got a penny. The other, Gene Moran, was promised equipment so he could DJ dances, but never got a thing. Gene had a great voice, was ambitious and smart and not long after I left KBBA he was hired by KKYK-FM 104, which at the time was Little Rock’s top-rated pop station. He started part-time there, but quickly worked his way up to evening jock. We worked together again a few years later in Jonesboro when the guy who had been KKYK’s GM was brought in to manage KJBR after it had been sold. Gene went on to pick up the radio tradition of moving all over and worked at some big stations.

After a few months of hardly getting any money, my dad, concerned I was being ripped off, called John Riddle. I’m sure he was diplomatic, but also very direct in asking why I wasn’t being paid. He was concerned that I, a 17-year-old, was having to drive 45 minutes on Interstate 30, including during the afternoon rush hours, working five nights a week while still a junior in high school. If I was making that kind of sacrifice, I needed to be fairly compensated the minimum wage I was promised of $3.35 an hour. When I saw Riddle a few hours after my dad called, he said he understood my dad’s concerns and would try to pay me more regularly. But he also reiterated the station’s dire financial situation.

Realizing that KBBA wasn’t going to work out, I started sending tapes and resumes to other stations. One of those was the other radio operation in Benton, which was an AM-FM combo started by former KBBA partner Preston Bridges. KAKI-FM 107.1 was an adult contemporary station that leaned heavily on oldies, while KGKO-AM 850 was automated adult standards.

A 1989 bumper sticker for KAKI-FM 107.1 in Benton.

I met with the program director who said he needed another part time DJ on the FM station and offered to let me have an on air audition. On June 26, 1989, I sat in with one of its DJs who showed me how to operate the equipment, then I hosted an hour, introducing and back announcing songs, and took one commercial break.

The station seemed professional with decent equipment and a full CD library provided by a radio programming service. Everything seemed to go well and I was optimistic I would get hired, but didn’t hear back from the PD.

AUDIO: On the air for an hour playing rock and oldies on KAKI-FM 107.1 in Benton, June 21, 1989 at about 9 p.m.

I learned two weeks later that most of the air staff, including the program director, had lost their jobs. The company had just learned a request to increase the power of the FM signal had been approved by the FCC, which would allow it to enter the Little Rock market. The positions were cut to save money for the upgrade, which involved moving the frequency to 106.7 FM. The Bridges family soon sold the FM, but kept the AM station for a couple more decades.

With that station ruled out, I applied to KLRA in England, Arkansas, which was an AM/FM simulcast. I had a job interview and was offered a position, so I gave KBBA what I felt was a very generous one-week notice that I was leaving. John Riddle said he would try to get together some of the money I was owed, but it seemed he spent the remaining week avoiding me. On my final day he wasn’t there when I arrived, so I called his home and got his answering machine. I left a message but didn’t get a call back. I wasn’t really surprised.

At the front door to KBBA on August 14, 1989.

I was never especially angry at Riddle because it seemed like he was trying hard to get advertising and sustain the station, but wasn’t successful. I was, however, bothered by how he misled the staff, especially high school kids. Or maybe he sincerely believed he could turn the situation around. The era for small AM stations like KBBA had passed and it was challenging to draw a large audience, especially with stronger stations from Little Rock that had much larger staffs that could produce better programming.

While I may not have been happy at the time, it was good to start at a small station. For most people on the air, it takes experience to get better. Listening to my tapes from KBBA, I sounded terrible. Another benefit was that this was where I was first exposed to the Arkansas Radio Network, running its newscasts at 55 minutes after each hour. Four years later I began working for the network and its flagship station KARN-AM 920 in Little Rock.

Within a year of me leaving, KBBA went off the air. It would remain dark for a couple of years until I saw in the April 17, 1992 issue of the trade paper Radio & Records that KBBA had been sold for a mere $7,500. The sale of Benton Broadcasting Service, owned by Dale and John Riddle, was overseen by bankruptcy trustee Richard Cox. The buyer was Bernard Bottenberg of Topeka, Kansas. The station would eventually come back on the air with different call letters and has gone through several incarnations since.

NEXT: KLRA – England, Arkansas

Revised Jan. 13, 2025